“Increasing compute for training makes models smarter &

Increasing compute for long thinking makes the answer smarter”

The statement encapsulates a widely recognized principle in AI development. The concept aligns with the understanding that both training and inference phases of AI models benefit from increased computational resources, albeit in different ways.

🧠 Training Compute: Building Smarter Models

During the training phase, AI models learn from vast datasets, adjusting their internal parameters to capture patterns and knowledge.

Increasing computational power during this phase allows for:

- Larger Models: More parameters can be trained, enabling the model to capture more complex patterns.

- Extended Training: Models can be trained over more data and for more epochs, improving generalization.

- Enhanced Performance: Empirical scaling laws demonstrate that model performance improves predictably with increased compute, data, and model size.

This relationship is detailed in studies on neural scaling laws, which show how performance metrics like loss decrease as compute resources increase during training.

🧠 Inference Compute: Enhancing Answer Quality

Inference refers to the model’s application phase, where it generates outputs based on new inputs. Allocating more compute during inference can lead to:

- Longer Context Handling: Processing longer input sequences for more coherent and contextually relevant outputs.

- Improved Reasoning: Allowing the model to perform more complex computations, leading to better problem-solving capabilities.

- Dynamic Computation: Techniques like test-time compute scaling enable models to allocate resources adaptively based on the complexity of the task

Research indicates that increasing compute during inference can enhance model performance, especially in tasks requiring complex reasoning.

🔄 Summary

In essence, increasing compute during training equips AI models with greater capabilities, while allocating more compute during inference allows them to utilize these capabilities more effectively to produce smarter answers.

NVIDIA

Founded in 1993, NVIDIA is the world leader in accelerated computing.

Our invention of the GPU in 1999 sparked the growth of the PC gaming market, redefined graphics, revolutionized accelerated computing, ignited the era of modern AI, and is fuelling industrial digitalization across markets.

NVIDIA is now a full-stack computing infrastructure company with data-center-scale offerings that are reshaping industry.

AI is advancing at light speed as agentic AI and physical AI set the stage for the next wave of AI to revolutionize the largest industries.

Founder and CEO: Jensen Huang (1993)

- Companies and countries around the world are building NVIDIA-powered AI factories to process, refine, and manufacture intelligence from data

- CUDA offers developers a powerful toolkit with over 400 libraries, 600 AI models, numerous software development kits

- Blackwell is one of the most important products in our history, boasting technologies that power AI training and real-time large language model inference for models scaling up to 10 trillion parameters.

1. Core Revenue Segments

Data Center

- Products: GPUs for AI, deep learning, and data analytics (e.g., H100, A100).

- Customers: Cloud service providers (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud), research institutions, enterprises.

- Growth Driver: AI adoption, especially large language models (LLMs), generative AI, and high-performance computing (HPC).

Gaming

- Products: GeForce GPUs, gaming laptops, and accessories.

- Customers: Consumers, PC gamers, and OEMs.

- Revenue Model: GPU sales, gaming platform services (like GeForce NOW), and software (e.g., DLSS, Reflex).

Professional Visualization

- Products: GPUs for designers, engineers, and creatives (e.g., RTX A6000).

- Use Cases: 3D modelling, video production, CAD software acceleration.

- Customers: Enterprises in media, architecture, and design.

Automotive

- Products: NVIDIA DRIVE (hardware + software stack for autonomous vehicles).

- Customers: Automotive OEMs and suppliers (e.g., Mercedes-Benz, BYD).

- Emerging Revenue: AI cockpit systems and autonomous driving platforms.

OEM & Other

- Products: Entry-level GPUs, embedded systems, and other licensing.

- Role: Legacy and niche markets; less significant than core areas.

2. Platform and Software Focus

NVIDIA is increasingly becoming a platform company, not just a chipmaker:

- CUDA: Proprietary parallel computing platform used widely in AI and scientific computing.

- NVIDIA AI Enterprise: Software suite for training, deploying, and managing AI workflows.

- Omniverse: A 3D collaboration and simulation platform for industrial digital twins.

- DGX Systems: Turnkey AI supercomputers combining hardware + software stack.

3. Business Model Mechanics

- Fabless Design: NVIDIA designs its chips but outsources manufacturing to foundries like TSMC.

- Hardware + Software Integration: Creates higher margins and customer lock-in.

- Ecosystem Development: Encourages developers to build on CUDA and Omniverse, boosting long-term platform adoption.

- Subscription & Licensing: Software (AI Enterprise, Omniverse) is shifting toward recurring revenue.

🔧 1. Hardware Products

A. GPUs (Graphics Processing Units)

- Data Center / AI:

- H100 (Hopper) – Flagship GPU for AI and large language models.

- A100 (Ampere) – Widely used in AI training and inference.

- L40 / L40S – High-performance GPUs for AI and visualization workloads.

- Grace Hopper Superchip – CPU-GPU combo optimized for AI and HPC.

- Gaming:

- GeForce RTX Series (e.g., RTX 4090, RTX 4080) – Consumer GPUs for gaming and content creation.

- GeForce GTX Series – Older generation gaming GPUs.

- Professional Visualization:

- RTX A6000 – Workstation GPU for design, engineering, and content creation.

- Quadro Series – High-end GPUs for professionals (branding phased into RTX).

B. Full Systems

- DGX Systems – AI supercomputers combining NVIDIA GPUs with software.

- HGX Platforms – Modular server platforms used by hyperscalers.

- OVX Systems – Built for digital twins and industrial simulations using Omniverse.

🧠 2. Software & Platforms

A. AI & Machine Learning

- CUDA – Parallel computing platform and API.

- cuDNN, TensorRT – Deep learning libraries optimized for NVIDIA hardware.

- NVIDIA AI Enterprise – Full software suite for AI development and deployment.

B. Visualization & Simulation

- Omniverse – Platform for real-time 3D collaboration and digital twins.

- RTX Remix – AI tools for remastering old video games.

C. Cloud & Edge

- NVIDIA AI Foundry Services – For building custom generative AI models.

- NIM (NVIDIA Inference Microservices) – Prebuilt microservices for model deployment.

🚗 3. Automotive & Embedded

- NVIDIA DRIVE – Hardware + software platform for autonomous driving:

- DRIVE Thor / DRIVE Orin – SoCs for autonomous vehicle compute.

- DRIVE Hyperion – Reference architecture for self-driving cars.

- Jetson – AI edge computing modules for robotics, drones, and IoT:

- Jetson Orin Nano / Xavier / AGX Orin

📡 4. Networking

- NVIDIA Mellanox (acquired 2020):

- InfiniBand and Ethernet switches/adapters for high-speed data center networking.

- BlueField DPUs (Data Processing Units) – Smart NICs for offloading tasks from CPUs in data centers.

Blackwell is NVIDIA’s next-generation GPU architecture announced in 2024 and is crucial to its future roadmap, especially for AI and data centers. Blackwell is the successor to the Hopper architecture (used in the H100) and underpins NVIDIA’s most advanced GPUs for AI workloads.

🔧 Major Blackwell Products:

🔹 B100

- Direct successor to the H100.

- Built for training and inference of large language models (LLMs).

- Includes major improvements in energy efficiency, FP8 performance, and multi-GPU scaling.

🔹 GB200 (Grace Blackwell Superchip)

- Combines a Blackwell GPU with a Grace CPU (ARM-based).

- Designed to address the memory bottleneck in training massive models.

- Target: cloud AI infrastructure, hyperscalers, LLMs like GPT and Claude.

| Architecture | Product | Status | Key Use Case |

| Hopper | H100 | Widely Deployed | Training/inference of LLMs, HPC |

| GH200 (Grace + Hopper) | Deployed | Large-scale AI, supercomputing | |

| Blackwell | B100 | Launching (2024–25) | Next-gen AI training, more efficient |

| GB200 | Announced | Combines Grace CPU + Blackwell GPU |

Why Blackwell Matters:

- 2× performance vs H100 (esp. for LLMs)

- Up to 30x energy efficiency improvements

- Designed for scaling across GPU clusters

- Already pre-ordered by AWS, Microsoft, Meta, Google Cloud

What Investors Ask Most About NVIDIA ?

Growth Sustainability & AI Demand

- Can NVIDIA maintain its rapid growth?

- Is the AI boom already priced into the stock?

Geopolitical Risks & China Exposure

- How will U.S.-China tensions impact NVIDIA?

- What is the threat from Chinese competitors?

Revenue Concentration & Customer Dependence

- Is revenue too concentrated among a few customers?

Regulatory Scrutiny & Legal Challenges

- What are the implications of antitrust investigations?

- How is NVIDIA addressing past legal issues?

Financial Management & Capital Allocation

- How is NVIDIA managing its capital expenditures?

- What is the impact of the recent stock split?

Product Innovation & Competitive Edge

- How will new architectures like Blackwell and Rubin shape NVIDIA’s future?

- Is NVIDIA’s software ecosystem a sustainable moat?

NVIDIA Architecture Roadmap (Past → Future)

| Architecture | Codename | Launch Year | Key Products | Focus Areas |

| Volta | V100 | 2017 | Tesla V100 | AI training, HPC |

| Ampere | A100 | 2020 | A100 | AI training/inference, HPC |

| Hopper | H100 | 2022 | H100, H200 | LLMs, AI training, HPC |

| Blackwell | B100 | 2024 | B100, B200 | Generative AI, LLMs |

| Rubin | R100 | Expected 2026 | R100, Rubin Ultra | Next-gen AI, HPC |

| Feature | Hopper (H100) | Blackwell (B100/B200) |

| Transistor Count | ~80 billion | ~208 billion |

| AI Performance (FP8) | ~4 PFLOPS | Up to 20 PFLOPS |

| Memory | HBM3 | HBM3e |

| Interconnect Bandwidth | ~900 GB/s | Up to 10 TB/s |

| Energy Efficiency | Baseline | Up to 25x improvement |

| Transformer Engine | First-generation | Second-generation |

| Decompression Engine | Not present | Included |

The transition from Hopper to Blackwell marks a substantial leap in performance and efficiency. Blackwell’s advancements cater to the escalating demands of AI workloads, offering enhanced performance and efficiency. Rubin is anticipated to succeed Blackwell, introducing significant enhancements in memory bandwidth and compute performance.

Compute Performance: Anticipated to deliver up to 1.2 ExaFLOPS of FP8 performance, marking a 3.3x improvement over Blackwell.

🧩 Strategic Positioning and Market Impact

NVIDIA’s architectural advancements are not just technological feats but strategic moves to maintain and extend its market leadership:

- Annual Release Cadence: Accelerating innovation cycles to meet the rapid evolution of AI workloads.

- Ecosystem Integration: Tight coupling of GPUs with CPUs (e.g., Grace and Vera) and networking solutions (e.g., NVLink, CX9) to offer comprehensive platforms.

- Market Leadership: Continued dominance in AI and HPC sectors, with widespread adoption across major cloud providers and enterprises.

These strategies ensure NVIDIA remains at the forefront of AI and HPC innovation.

What We Know About Rubin (as of 2025)

- Rubin is confirmed in NVIDIA’s long-term roadmap.

- Likely to be paired with Vera, a new Grace CPU successor.

- Will further optimize AI model training and inference, possibly for post-LLM AI models (e.g., multi-modal systems, agentic AI).

- May push NVIDIA further into custom silicon AI clusters for hyperscalers.

🛠️ Expected Features (Speculative):

- Better energy-per-watt than Blackwell

- More efficient multi-GPU communication

- Possibly new memory technologies (e.g., CXL, HBM4)

🧠 NVIDIA’s AI Architecture Strategy:

- Blackwell (2024–2025): Dominating AI compute now (H100 → B100).

- Rubin (2026+): Ensuring leadership as model and compute demands scale further.

- Yearly cadence: Following a tick-tock cycle: architecture → refinement → new architecture

2. Gaming GPUs (GeForce)

| Architecture | Product Series | Use Case |

| Ada Lovelace | RTX 40 Series (4090, 4080, etc.) | High-end gaming, ray tracing |

| Ampere | RTX 30 Series | Mid-tier / legacy gaming |

3. Professional & Visualization

| Product | Use Case |

| RTX A6000 / A5000 | 3D rendering, design, CAD |

| Omniverse | Industrial simulation, digital twins |

NVIDIA Data Center growth drivers

- Broad data center platform transition from general-purpose to accelerated computing – The $1T installed base of general-purpose CPU data center infrastructure is being modernized to a new GPU-accelerated computing paradigm

- Emergence of AI factories—optimized for refining data and training, inferencing, and generating AI

- The entire computing stack has been reinvented—from CPU to GPU, from coding to machine learning, from software to generative AI.

- Computers generate intelligence tokens, a new commodity.

- A new type of data center, AI factories, is expanding the data center footprint to $2T and beyond in the coming years.

- Eventually, companies in every industry will operate AI factories as the digital twin of their workforce, manufacturing plants, and products. A new industrial revolution has begun

- Broader and faster product launch cadence

Nvidia’s data center revenue is $101.5 billion, 77.8% of its total revenue

In the same period, global capital expenditures (capex) on data centers by major technology companies—including Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and Meta—are projected to exceed $300 billion.

Based on these figures, Nvidia’s data center revenue represents roughly 33.8% of the total data center capex by these leading tech firms.

This significant proportion underscores Nvidia’s pivotal role in supplying the hardware—particularly GPUs—that power the infrastructure of modern data centers, especially those dedicated to artificial intelligence and high-performance computing.

It’s important to note that this percentage is a broad estimate. Not all of Nvidia’s data center revenue comes exclusively from these companies, and not all data center capex is allocated to Nvidia products. Nevertheless, the figure highlights the substantial impact Nvidia has on the data center industry.

NVIDIA Gaming growth drivers

- Rising adoption of NVIDIA RTX in games

- Expanding universe of gamers and creators

- Gaming laptops and generative AI on PCs

- GeForce NOW cloud gaming

Professional Visualization

- Generative AI adoption across design and creative industries

- Enterprise AI development, model fine-tuning, cross-industry

- Expanding universe of designers and creators

- Omniverse for digital twins and collaborative 3D design

Automotive

- Over 40 customers including 20 of top 30 EV makers, 7 of top 10 truck makers, 8 of top 10 robotaxi makers

- Adoption of centralized car computing and software-defined vehicle architectures

Products

This chart visualizes the energy efficiency improvements of NVIDIA’s GPU architectures over time, specifically in terms of Joules per Token (J/Token). It shows how much energy is required to process one token — a unit commonly used in AI and NLP tasks like those in large language models (LLMs).

Breakdown by Architecture:

- Kepler (2014):

🔋 42,000 J/Token – Extremely high energy consumption. - Pascal:

🔋 17,640 J/Token – Major improvement, but still energy-intensive. - Volta:

🔋 1,200 J/Token – A significant leap in efficiency. - Ampere:

🔋 150 J/Token – More than 8x improvement from Volta. - Hopper:

🔋 10 J/Token – Efficiency increases dramatically. - Blackwell (2024):

🔋 0.4 J/Token – State-of-the-art, about 25x better than Hopper.

This chart titled “Blackwell Giant Leap in Inference Performance” visually compares the inference performance of different NVIDIA systems across two axes:

- Y-axis (Vertical): Throughput, measured in Transactions Per Second (TPS) per Megawatt (MW). Higher is better — it means more inference operations are completed per unit of energy.

- X-axis (Horizontal): TPS for a single user — essentially a proxy for latency or responsiveness. Further right is better for smart, fast-responding AI, because it means faster response times for individual queries.

Key Components and What the Chart Shows

Systems Compared

Several NVIDIA configurations are plotted:

- Hopper Dynamo

- Blackwell NVL8 (FP8 and FP4 precision)

- Blackwell NVL72 (FP4)

- Blackwell Dynamo NVL72 (FP4)

Each curve represents a specific hardware setup and inference precision mode:

- FP8 (Floating Point 8-bit): Prioritizes energy efficiency and throughput.

- FP4 (Floating Point 4-bit): Offers higher responsiveness and memory efficiency for ultra-large models.

Interpretation of Curves

Each curve maps throughput vs. responsiveness:

Hopper Dynamo

- Located in the bottom-left corner.

- Lower TPS and lower throughput.

- Represents the previous generation — serves as a baseline for comparison.

Blackwell NVL8 (FP8)

- Sharp increase in throughput compared to Hopper.

- Less responsive per user than FP4, but very energy-efficient.

- Ideal for high throughput, low-latency environments like batch inference.

Blackwell NVL8 (FP4)

- Trades a bit of throughput for better per-user responsiveness.

- Shows the flexibility of the NVL8 platform with different precision modes.

Blackwell NVL72 (FP4)

- Much farther along the x-axis (smart, responsive AI) and still maintains high throughput.

- Indicates that this configuration supports larger models or more demanding inference tasks with better user experience.

Blackwell Dynamo NVL72 (FP4)

- Furthest on the x-axis (TPS for 1 user) and maintains strong throughput.

- Represents the pinnacle of performance among all plotted systems.

- Best suited for real-time, large-scale inference — such as for AI agents, chatbots, and LLMs with many concurrent users.

Why This Matters

For AI deployment, especially with large language models or multimodal AI:

- Low latency (right side of x-axis) is crucial for interactive applications.

- High throughput per megawatt is essential for scaling inference economically and sustainably.

This graph illustrates how NVIDIA’s Blackwell platform advances both fronts — enabling AI systems that are not just faster, but also greener and more responsive.

“Blackwell 25X Hopper”, gives a deeper and more technical breakdown of the inference performance gains achieved by NVIDIA’s Blackwell architecture over the previous generation, Hopper. Here’s a detailed analysis:

🧠 What the Chart Represents

Axes:

- Y-Axis (Vertical): Throughput measured in Transactions Per Second (TPS) per Megawatt (MW). Higher is better — more output per unit of energy.

- X-Axis (Horizontal): TPS for a single user — an indicator of response time or latency. Further right means faster and more responsive AI.

🔄 Compared Technologies

📦 Hopper FP8 / NVL8 / Dynamo (Left shaded area)

- Previous generation baseline.

- Constrained in both energy efficiency and latency.

- Systems cluster in the lower-left quadrant of the chart — low throughput and slower response times.

🚀 Blackwell FP4 / NVL72 / Dynamo (Right gold curve)

- New generation of inference architecture.

- Achieves 25x performance per watt over Hopper in this configuration.

- Dominates in both throughput and user responsiveness.

🧪 Breakdown of Conditions and Color Coding

Each point on the Blackwell performance curve includes a label describing the configuration used:

🟠 Orange: EP8 / EP32 configurations

- High batch sizes (e.g. 3072, 1792).

- “Disagg Off” indicates no disaggregated memory, which typically means memory is tightly integrated (low latency).

- These points dominate throughput (top-left of curve).

Orange Labels (Top Left)

Examples:

- EP8, Batch 3072, Disagg Off

- EP32, Batch 1792, Disagg Off

These setups are:

- Using larger batches → good for processing lots of inputs at once (e.g., summarizing 1,000 emails).

- Disagg Off = Using local memory for faster speed.

- These are super energy-efficient but slow to respond to a single user.

🔑 Use Case: Mass AI tasks, not real-time.

🟢 Green: EP64, Batch 896 to 128, Disagg Off

- These represent moderate batch sizes with 64-engine parallelism.

- Showcases the scalability of throughput as batch size scales down.

- Still not tuned for individual latency — they optimize for overall energy efficiency.

Examples:

- EP64, Batch 896

- EP64, Batch 256

These are still doing batch processing, but with smaller groups.

- Less efficient than orange, but slightly faster.

- They balance between throughput and response.

🔑 Use Case: Medium-speed apps — not fully real-time, not fully batch.

🔵 Cyan/Teal: EP64+EP4, various batch sizes, “Context”, “MTP On”

- These configurations introduce contextualized inference (e.g., 26% to 1% context).

- MTP On likely refers to a memory or multi-tasking optimization (e.g., Memory Traffic Prediction).

- As batch size and context reduce, these points move further right — more optimized for real-time interaction.

Examples:

- EP64+EP4, Batch 64, 26% Context, MTP On

- EP64+EP4, Batch 8, 7% Context, MTP On

Now we’re entering real-time response territory:

- These models are designed to reply quickly to user prompts (e.g., chatbot messages).

- The Context % shows how much memory from previous messages is used. Less context = faster.

🔑 Use Case: Chatbots, AI agents, personal assistants

🟣 Purple/Pink: TEP + EP4, ultra-low batch sizes and minimal context

- TEP16 and TEP8 indicate the use of Token Efficient Parallelism.

- Target the extreme end of real-time AI — like AI agents responding instantly to prompts.

- These are closest to the bottom-right: maximum responsiveness with reasonable throughput.

Examples:

- TEP8+EP4, Batch 4, 1% Context, MTP On

- TEP16+EP4, Batch 2, 1% Context

These are the fastest and most responsive AI setups:

- Tiny batch size = instant reply.

- Minimal memory (1% context) = lightning fast.

- TEP = Token Efficient Pipeline, perfect for streaming tokens one-by-one (like how ChatGPT responds).

🔑 Use Case: Instant AI assistants, token-based LLMs

Batch size is the number of inputs (or data samples) the AI model processes at the same time.

| Batch Size | Use Case | Pros | Cons |

| Small (1–8) | Real-time apps (chatbots, games) | Fast response | Less efficient |

| Medium (16–128) | Hybrid workloads | Good balance | Some latency |

| Batch Size | Pros | Cons |

| Small (1–4) | Fast reply per user | Less GPU efficiency |

| Medium (16–64) | Some efficiency gain | Slightly more latency |

| Large (128+) | High GPU use | Way too slow for chat — not used here |

Batch Size = Number of Inputs (Requests) – Think of it as how many separate queries or users are processed at the same time.

Tokens = Size of Each Input – Number of text units per input i.e. Tokens are chunks of text — like words or parts of words.

| Batch Size | Tokens per Input | Total Work |

| 4 | 100 tokens | 400 tokens total |

| 64 | 50 tokens | 3,200 tokens total |

| 1 | 2,000 tokens | 2,000 tokens total |

What Does Affect Performance? Performance depends on:

- ✅ Batch size (number of parallel inputs)

- ✅ Number of tokens per input (input length)

- ✅ Model size (e.g., GPT-3, GPT-4)

- ✅ Precision (FP4, FP8, etc.)

- ✅ Context window (how much memory the model has to look back)

Context – It means that the model is using past conversation or prior tokens (called “context”) to help generate the next response — and that context takes up 52% of the total token window available.

Most large language models have a context window, which is the total number of tokens they can “see” at one time. For example:

- GPT-4 has context windows up to 128k tokens

- GPT-3.5 might use up to 4k or 16k tokens

| Context % | Behaviour | Use Case |

| Low (1–5%) | Fast, efficient | Chatbots, token-by-token response |

| Medium (10–30%) | Balanced | AI assistants with memory |

| High (50%–90%) | Slower, smarter | Research, document Q&A, memory-heavy agents |

Understanding context size is important for:

- Avoiding repetition

- Keeping long conversations coherent

- Knowing when the AI might “forget” earlier parts (which can happen in long documents or multi-turn chats with older models)

Context & tokens used – “Context is 1–5% for fast, efficient chatbot-type behavior.”

And now I also said: “I retain 100% of our entire conversation.”

So… how can both be true?

In short chat, ChatGPT uses 100% of the context (because it’s short). In high-performance systems, models may use only 1–5% of recent context to keep response times low and energy use efficient.

This chart shows how token usage shifts as chat length increases, using a model with a 128,000-token context window (like GPT-4 Turbo):

- 🔹 Short chats (500–2,000 tokens): Almost all the past messages (context) are retained. There’s plenty of room for new input.

- 🔹 Medium chats (8,000 tokens): About half the window is used for context; the other half is available for new messages.

- 🔹 Long chats (32,000–128,000 tokens): The system begins to truncate older context, keeping only the most recent ~10% of tokens for context, so it can handle new input efficiently.

This balancing act ensures the model stays responsive while maintaining coherence — even in very long conversations.

A larger context window lets the model “remember” way more of your chat, making it ideal for:

- Long technical discussions

- Multi-document analysis

- Persistent memory in AI agents

📊 Key Takeaways

🔹 1. Blackwell Dominates the Entire Spectrum

- From batch inference (top-left) to real-time LLM interactions (bottom-right).

- The chart shows a smooth scalability curve, which is critical for data centers running both types of workloads.

🔹 2. 25X Energy Efficiency Boost

- The Hopper region is boxed in the bottom-left, showing its limits.

- Blackwell’s curve extends far beyond that — offering 25 times better performance per watt across various configurations.

🔹 3. Flexibility Across Use Cases

- Blackwell isn’t just about raw power — it can be fine-tuned for:

- Massive batch inference

- Chatbots/AI assistants

- Streaming, token-based models (e.g., LLMs)

- The diverse configurations (EP32, EP64+EP4, TEP16, etc.) allow precise tuning.

⚡ Terminology Breakdown

| Term | Meaning |

| EP | Execution Pipe — likely a measure of parallel inference lanes |

| TEP | Token Efficient Pipeline — optimized for LLM token processing |

| Batch | Number of inputs processed together — larger batch = better throughput |

| Disagg Off | Disaggregated memory off — using unified memory for speed |

| MTP On | Likely “Memory Traffic Prediction” or related optimization |

| Context % | Portion of context relative to input, affecting inference depth and latency |

🧠 Why This Matters

The chart illustrates how Blackwell is not just faster — it’s adaptable:

- For data centers, it’s a huge energy and cost saver.

- For AI services, it ensures fast, real-time interaction at scale.

- For LLMs, it allows tradeoffs between context size, token responsiveness, and energy

This chart looks complex, but once we break it down, it tells a powerful story about how NVIDIA’s Blackwell platform is a massive leap forward for AI model performance.

Major trends

Today, two transitions are occurring simultaneously—accelerated computing and generative AI—transforming the computer industry,

Accelerated computing

A full-stack approach: silicon, systems, software (not just superfast chip). Requires full-stack innovation— optimizing across every layer of computing

- Chip(s) with specialized processors

- Algorithms in acceleration libraries

- Domain experts to refactor applications

Accelerated computing is needed to tackle the most impactful opportunities of our time—like AI, climate simulation, drug discovery, ray tracing, and robotics

AI Driving a Powerful Investment Cycle and Significant Returns

- AI Agents will take action to automate tasks at superhuman speed, transforming businesses and freeing workers to focus on other tasks.

- Copilots based on LLMs will generate documents, answer questions, or summarize missed meetings, emails, and chats—adding hours of productivity per week. Specialized for fields such as software development, legal services or education and can boost productivity by as much as 50%.

- Social media, search, and e-commerce apps are using deep recommenders to offer more relevant content and ads to their customers, increasing engagement and monetization.

- Creators can generate stunning, photorealistic images with a single text prompt—compressing workflows that take days or weeks into minutes in industries from advertising to game development.

- Call center agents augmented with AI chatbots can dramatically increase productivity and customer satisfaction.

- Drug discovery and financial services are seeing order-of-magnitude workflow acceleration from AI.

- Manufacturing workflows are reinvented and automated through generative AI and robotics, boosting productivity.

- Generative AI is trained on large amounts of data to find patterns and relationships, learning the representation of almost anything with structure. The era of generative AI has arrived, unlocking new opportunities for AI across many different applications. It can then be prompted to generate text, images, video, code, or even proteins. For the very first time, computers can augment the human ability to generate information and create.

- The next AI wave is physical AI—models that can perceive, understand, and interact with the physical world. Physical AI will embody robotic systems—from autonomous vehicles to industrial robots and humanoids, to warehouses and factories

Three computers and software stacks are required to build physical AI: NVIDIA AI on DGX to train the AI model, NVIDIA Omniverse on OVX to teach, test, and validate the AI model’s skills, and NVIDIA AGX to run the AI software on the robot

NVIDIA AGX refers to a family of high-performance computing platforms designed for AI-powered autonomous machines and embedded systems. The AGX lineup includes the Jetson AGX Xavier and Jetson AGX Orin modules, each tailored for specific applications ranging from robotics to autonomous vehicles.

- Perception AI – e.g., image classification, speech recognition

- Generative AI – e.g., text/image generation (like GPT, DALL·E)

- Agentic AI – decision-making, planning, goal pursuit

- Physical AI – robotics, embodied agents in the real world

AI factories are a new form of computing infrastructure. Their purpose is not to store user and company data or run ERP and CRM applications. AI factories are highly optimized systems purpose-built to process raw data, refine it into models, and produce monetizable tokens with great scale and efficiency. In the AI industrial revolution, data is the raw material, tokens are the new commodity, and NVIDIA is the token generator in the AI factory.

CUDA Libraries

Unlike CPU general-purpose computing, GPU-accelerated computing requires software and algorithms to be redesigned. Software is not automatically accelerated in the presence of a GPU or accelerator.

NVIDIA CUDA libraries encapsulate NVIDIA-engineered algorithms that enable applications to be accelerated on NVIDIA’s installed base. They deliver dramatically higher performance—compared to CPU-only alternatives—across application domains, including AI and high-performance computing, and significantly reduce runtime, cost, and energy, while increasing scale.

Energy consumption and product evolution

Amdahl’s Law is a formula in computer science that describes the theoretical maximum speedup achievable by parallelizing a task. It states that the overall speedup is limited by the portion of the task that cannot be parallelized, even if other parts of the task are significantly improved. Essentially, the bottleneck of the task, the part that can’t be parallelized, dictates the overall performance improvement.

Key Points:

- Limited Speedup: The law demonstrates that adding more processors or resources will not always lead to a linear increase in performance.

- Serial Fraction: The portion of a task that cannot be parallelized (often referred to as the serial fraction) is a critical factor in determining the maximum speedup.

- Maximum Speedup: Even with a large number of processors, the overall speedup will never exceed the inverse of the serial fraction.

- Parallelizable Fraction: The portion of the task that can be parallelized determines the potential for speed improvement

Tokens refer to the outputs of AI model inference—specifically, the smallest units of data that large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT process and generate during operation.

What are tokens, really?

- In natural language processing (NLP), a token is typically a word, part of a word, or even a character, depending on how the model is trained.

- For example – The sentence “AI is powerful.” might be broken into 4 tokens: [“AI”, ” is”, ” powerful”, “.”].

- During inference (when an AI model generates text), these tokens are:

- Consumed as input tokens.

- Produced as output tokens.

Why are tokens considered a “commodity”?

In this metaphor:

- Data is the raw material (just like crude oil).

- AI models are like refineries.

- Tokens are the refined product—the thing you can sell, consume, or use for value.

Tokens are monetizable because:

Companies pay for the generation and processing of tokens. The more tokens a system can generate quickly and cost-effectively, the more value it can produce.

For example, OpenAI or any provider might charge per 1,000 tokens of input/output.

And NVIDIA? NVIDIA is called the “token generator” because:

- Their GPUs (graphics processing units) are the core hardware powering AI factories. These chips run the computations that generate tokens during AI model inference and training. The better and faster their chips, the more tokens can be produced—hence the “token generator” metaphor.

Summary

In this context, tokens = the fundamental unit of AI-generated output, and they’re likened to a commodity in the AI economy, produced in vast numbers by high-performance computing systems like those powered by NVIDIA hardware.

Price of tokens

The price of tokens depends on the AI service provider, the model used, and the usage type (e.g. input vs output). Here’s a breakdown using OpenAI’s pricing as an example (as of early 2025):

OpenAI GPT-4 (Turbo) Pricing Example

(Prices per 1,000 tokens)

| Model | Input Tokens | Output Tokens |

| GPT-4 Turbo (128k context) | $0.01 | $0.03 |

| GPT-3.5 Turbo | $0.001 | $0.002 |

1,000 tokens ≈ 750 words (roughly 3-4 paragraphs of English text).

What does this mean in real use?

If you send a prompt with 500 tokens and get a response of 700 tokens:

- Total tokens used = 1,200 tokens

- With GPT-4 Turbo:

- Input: 500 × $0.01 / 1,000 = $0.005

- Output: 700 × $0.03 / 1,000 = $0.021

- Total = $0.026

Enterprise & Custom Models

- For large-scale AI factories or enterprise customers, pricing can differ.

- Providers like OpenAI, Anthropic (Claude), Google (Gemini), and Mistral may offer:

- Bulk pricing

- Dedicated infrastructure

- Token generation quotas

Why token prices matter

- They determine cost per request, especially in high-usage AI products.

- Companies building AI applications need to optimize token usage for profitability.

- NVIDIA’s role as a “token generator” ties to the idea that more efficient hardware means cheaper tokens.

GPUs require specialized software because of their fundamentally different architecture compared to CPUs. GPUs need specialized software because they operate differently from CPUs. To harness their parallel processing power, algorithms must be rewritten, memory must be managed differently, and dedicated APIs like CUDA must be used. Without these changes, the GPU remains idle—even if present.

GPUs are built for massively parallel operations, with thousands of smaller cores ideal for repetitive, data-parallel tasks (like matrix operations, image processing, etc.).

For a GPU to be effective, the software must identify and schedule operations that can run in parallel. CUDA libraries and frameworks provide tools and abstractions to rewrite software in a way that exposes this parallelism.

CPUs and GPUs often have separate memory spaces, and data must be explicitly transferred between them. Efficient GPU use requires careful memory management. GPU-aware software must manage these data transfers and optimize memory usage to avoid performance bottlenecks.

Move “up and to the right” on the chart — increasing both tokens per user (speed) and tokens across users (scale).

| Element | Description | Business Impact |

| Data | The input to train or run models | Foundational asset |

| Compute (FLOPS) | Determines processing speed | Higher = faster token generation |

| HBM Memory & Bandwidth | Limits or enables fast data access | Essential for low-latency AI |

| Architecture + Software | Optimizes resource usage | Better efficiency, more output per $ |

| Tokens/sec (Throughput) | Tokens produced across all users | Higher = greater monetizable volume |

| Tokens/sec (Latency) | Tokens delivered per user per request | Faster = better UX, higher retention |

| Revenue | Comes from charging per token | Scale directly = scale profit |

Just like traditional factories turned raw materials into products for sale, AI factories turn data into tokens, which are the billable product of modern computing.

NVIDIA and similar players are building the infrastructure to maximize token output. Every optimization in compute, memory, and architecture leads to higher revenue per watt, per chip, per rack.

AI Factory: The New Digital Industrial Model

⚙️ Analogy: AI as a Factory

- Raw Material → Data

- Factory Machines → GPUs + Memory + AI Models

- Refined Product → Tokens (AI-generated output)

- Output Unit → Tokens per second

- Revenue → Tied directly to how many tokens you produce and sell

The Three Scaling Laws

Pre-Training Scaling

- Traditional model scaling: increase data, model size, and compute during initial training.

- Fuels capabilities in perception and early generative tasks.

Post-Training Scaling

- Refers to improving models after initial training (e.g., via fine-tuning, RLHF, tool use).

- Critical for making models more useful, safe, and capable in nuanced tasks.

Test-Time Scaling (Long Thinking)

- Inference-time enhancements: allowing the model to think longer or use more compute dynamically during use.

- Examples: chain-of-thought reasoning, tool-assisted reasoning, external memory.

- Supports more agentic, deliberative, and planning-heavy tasks.

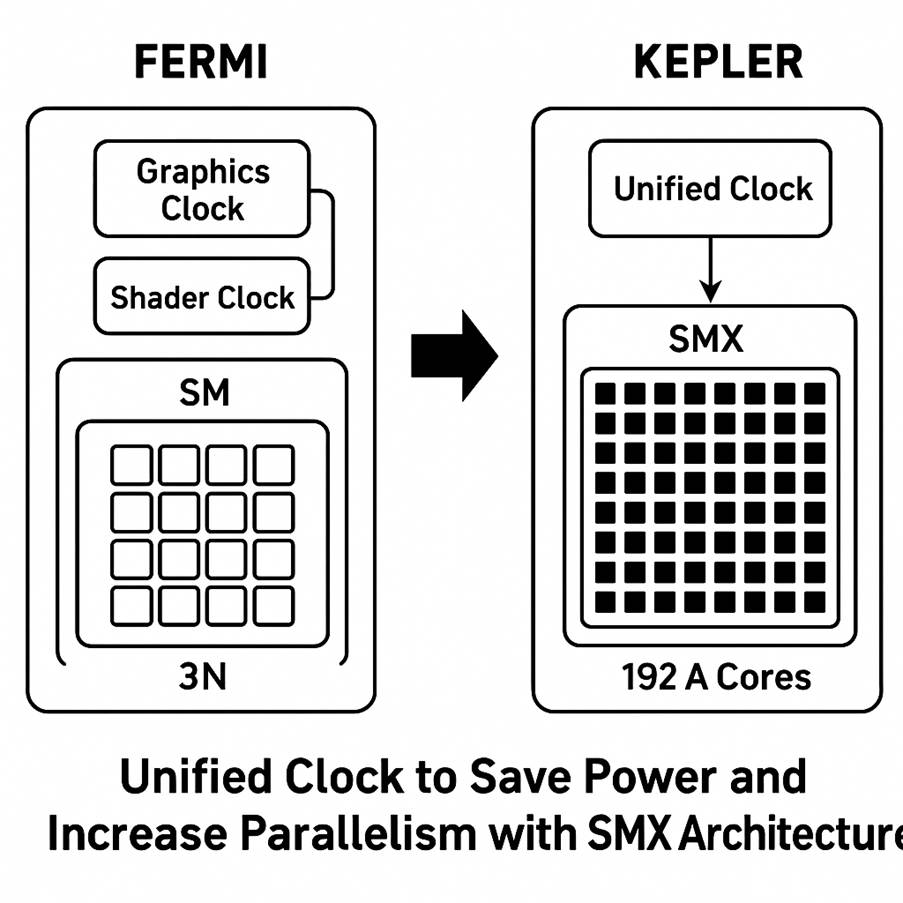

Kepler (2012) – 28 nm and a Focus on Efficiency

Introduced in 2012, Kepler was built on TSMC’s 28 nm process and succeeded the Fermi architecture. It was NVIDIA’s first design focused heavily on energy efficiency.

Kepler struck a balance between graphics and compute. It improved gaming performance while significantly advancing GPU computing. Its efficiency and new features (Hyper-Q, dynamic parallelism) made GPUs more attractive and easier to use in HPC clusters.

Overall, Kepler established a foundation that future architectures would build on, especially for making GPUs more general-purpose and energy-efficient.

New features: Kepler introduced several capabilities to improve GPU compute and parallel programming. Dynamic Parallelism allowed GPUs to spawn new work without CPU intervention, and Hyper-Q enabled multiple CPU threads or MPI processes to more efficiently share a GPU by feeding work into its queues in parallel. These features reduced CPU-GPU idle time and improved utilization in HPC applications.

Notable products: Consumer: GeForce GTX 680 was the first Kepler flaghip, later followed by GTX 780 and the first “GTX Titan” (2013) using a full GK110 chip with 2688 cores and 6 GB memory, which brought compute capabilities to a prosumer card.

Data Center: Tesla K20 and K20X accelerators (2012) were used in Oak Ridge’s “Titan” supercomputer and other HPC systems, delivering ~1.3 TFLOPS FP64 with much higher efficiency than Fermi GPUs. The later Tesla K40 (2013) and dual-GPU K80 (2014) gave increased memory (up to 12 GB per GPU) for HPC workloads. Kepler GPUs proved their worth in early deep learning as well – for instance, researchers leveraged GTX 680/770s (and even K20s) for training some of the first neural nets, though Kepler lacked dedicated tensor hardware.

Pascal (2016) – FinFET Performance Leap and Memory Innovation

Announced in 2016, Pascal marked a major generational jump, fabricated on 16 nm FinFET (TSMC) – a shrink from 28 nm that brought huge gains in transistor density and power efficiency

Pascal was introduced first in the Tesla P100 accelerator in April 2016, then in GeForce GTX 1080 for consumers a month later. It was the first architecture to feature HBM2 memory and NVIDIA’s high-speed NVLink interconnect in its HPC variant, while the consumer cards used improved GDDR5X memory.

Impact on AI, HPC, and graphics: Pascal set the stage for the AI boom. Researchers and companies adopted Pascal GPUs (like the DGX-1’s P100s) to train neural networks, and it was instrumental in the transition from CPU-only deep learning to GPU-accelerated deep learning across industry. Though still general-purpose cores, its FP16 capability hinted at specialized AI use. In HPC, P100 GPUs delivered big leaps in simulation and scientific computing, enabling GPU-based supercomputers to dominate the Top500. For graphics, Pascal GPUs increased performance per watt dramatically, making high-end gaming and VR more accessible, and features like SMP improved VR image quality. Pascal essentially bridged the gap between a pure graphics architecture and one ready for compute and AI, laying a foundation that the next architecture (Volta) would greatly expand on for AI acceleration.

VOLTA.

In late 2017, NVIDIA launched Volta, an architecture squarely aimed at compute and AI, though it carries the GeForce lineage forward from Pascal. Volta (GV100 GPU) was manufactured on a custom 12 nm TSMC process. It was NVIDIA’s first architecture to introduce specialized hardware beyond the traditional CUDA cores: namely, the Tensor Cores, which profoundly boosted deep learning performance.

Impact on AI/ML, HPC, and graphics: Volta was a watershed moment for AI/ML. It substantially reduced training times for neural networks – models that took weeks on Pascal could be trained in days on Volta. This enabled researchers to iterate faster and train larger, more complex models (Volta’s Tensor Cores were crucial in the AI breakthroughs around 2018–2019, such as image recognition improvements, machine translation, and the early transformers). In HPC, Volta continued NVIDIA’s disruption of supercomputing: V100s offered stellar FP64 performance and helped GPU-based systems dominate the top of the Top500 list, while also accelerating mixed-precision scientific computing and AI workloads for scientific research (folding in AI with traditional HPC). For graphics, although gamers didn’t get a Volta GeForce, the architectural advancements (like concurrency and tensor core acceleration) foreshadowed technologies that would soon enter gaming with Turing and later Ampere (e.g., DLSS – an AI upscaling feature – was made possible by Tensor Cores, which debuted in Volta). Overall, Volta firmly established that GPU architectures would henceforth cater not just to rendering graphics, but to accelerating AI at scale – a theme that continues through Ampere, Hopper, and Blackwell.

Ampere (2020) – Unified Architecture for CUDA, Tensor & Ray Tracing

In 2020, NVIDIA’s Ampere architecture sought to unify advances for both data center AI/HPC and consumer graphics. Succeeding Volta (and Turing on the consumer side), Ampere was manufactured on two process nodes: the A100 data center GPU used TSMC 7 nm, while GeForce RTX 30-series GPUs used a custom Samsung 8 nm process. The Ampere family thus covered everything from the largest AI supercomputers to gaming PCs, with shared architectural principles but some differences in implementation.

Relevance to AI/ML, HPC: Ampere (A100) was the dominant AI training and inference GPU of its time – it’s estimated that by 2022, the vast majority of machine learning model training computations were happening on NVIDIA Ampere GPUs in data centers. With its MIXED-precision and sparsity features, Ampere allowed training of larger models like GPT-3 with fewer GPUs or in less time than Volta would require. For HPC, A100’s strong FP64 (9.7 TFLOPS, ~1.25× V100) and huge memory made it ideal for HPC centers upgrading from V100 – many scientific computing sites integrated A100s for simulation and AI convergence workloads. Graphics and gaming: GeForce Ampere cards became very popular (notwithstanding supply issues during the 2020–2021 crypto-driven shortage). They enabled high-fidelity 4K gaming with ray tracing and were instrumental in pushing technologies like DLSS 2.0 (which uses the Tensor Cores to boost frame rates via AI upscaling). Ampere’s success in both arenas demonstrated the versatility of a GPU architecture that could accelerate traditional graphics and the new frontier of AI simultaneously.

Hopper (2022) – Data Center AI Beast with Transformer Engine

Unveiled in March 2022, Hopper (named after Grace Hopper) is an architecture designed exclusively for data center and compute, succeeding Ampere’s HPC role (while the Ada Lovelace architecture, launched in late 2022, catered to consumer GPUs). The flagship NVIDIA H100 GPU is built on a custom TSMC 4N process (optimized 4 nm) with around 80 billion transistors on a huge 814 mm² die

Hopper introduces significant new features to accelerate AI training, especially for large language models, and pushes the envelope in GPU computing performance and scalability.

Relevance and use cases: Hopper H100 quickly became the premium solution for cutting-edge AI labs and enterprise AI. Its introduction coincided with the explosion of large language models like GPT-3, and later GPT-4 – models which greatly benefit from Hopper’s Tensor engine and huge memory. For training giant models (hundreds of billions of parameters), H100 can reduce training times and also make feasible the real-time inference of those models using FP8. For example, NVIDIA reported up to 30× faster LLM inference on

This capability is transformative for deploying AI (e.g., chatbots, AI services) at scale. In HPC and scientific computing, H100’s FP64 is about 2× A100 (reaching ~20 TFLOPS FP64), and its DPX and other enhancements open GPUs to new workloads like genomics and dynamic programming tasks. Essentially, Hopper extends NVIDIA’s dominance in AI computing by not just throwing more cores at the problem but adding targeted hardware and architectural tweaks for AI and data-centric computing. It underscores the shift of GPUs from pure graphics to general-purpose compute devices tailored for AI. As such, Hopper (H100) has been adopted in top supercomputers (it’s a key part of the AI-focused Leonov and Alps systems, for instance) and in cloud GPU offerings where maximum performance is needed (OpenAI, Meta, etc., all source H100s for training their latest models). For completeness: Graphics impact: While Hopper itself didn’t directly impact gaming (since it wasn’t in GeForces), the architectural learnings did. The idea of large L2 caches and massive bandwidth was seen in Ada Lovelace (which increased L2 cache dramatically for GeForce 40-series, inspired partly by what was done in A100/H100 for compute). And some of Hopper’s improvements, like better scheduling and concurrent execution, continue to influence future consumer designs. But primarily, Hopper will be remembered as the AI-focused architecture that enabled the “AI factories” of the mid-2020s – specialized datacenters churning out AI models and services.

Blackwell (2024–2025) – Next-Gen Architecture for AI and Graphics

Blackwell is the codename for NVIDIA’s newest GPU architecture (named after mathematician David Blackwell), succeeding Hopper (data center) and Ada Lovelace (consumer). Announced in 2024, Blackwell GPUs target both the data center (for exascale AI and HPC) and the next generation of GeForce RTX 50-series graphics cards for consumers. This architecture continues NVIDIA’s trajectory of AI-centric design, while also doubling down on graphics performance, particularly ray tracing and neural rendering.

Blackwell Ultra: Scaling AI Performance (2025)

Announced in 2025, the Blackwell Ultra architecture represents a substantial leap in AI processing capabilities. Key features include:

- Dual-Die Design: Combining two GPU dies to increase computational density.

- Enhanced Memory: Up to 288 GB of HBM3e memory, facilitating larger AI models.

- Improved Performance: Achieving 20 petaflops of FP4 performance, doubling the capabilities of its predecessor, the Hopper architecture.

These advancements cater to the growing demand for AI applications requiring higher throughput and efficiency.

🔭 Vera Rubin Architecture: The Next Frontier (2026)

Scheduled for release in the second half of 2026, the Vera Rubin architecture is poised to redefine AI computing. Named after astronomer Vera Rubin, this architecture introduces:

- Vera CPU: Nvidia’s first custom-designed processor based on the Olympus core architecture.

- Rubin GPU: Delivering up to 50 petaflops of FP4 performance, more than doubling Blackwell Ultra’s capabilities.

- Advanced Memory: Utilizing HBM4 memory with 13 TBps bandwidth, significantly enhancing data throughput.

- NVLink 6 Interconnect: Providing 3,600 Gbps of bandwidth for efficient GPU-to-GPU communication.

The Vera Rubin platform is designed to support complex AI models, including those requiring advanced reasoning and decision-making capabilities

| Architecture | Codename | Year | Named After | Field / Contribution |

| Fermi | Fermi | 2010 | Enrico Fermi | Nuclear physics, quantum theory, father of the atomic bomb |

| Kepler | Kepler | 2012 | Johannes Kepler | Astronomy, planetary motion laws |

| Maxwell | Maxwell | 2014 | James Clerk Maxwell | Electromagnetism, Maxwell’s equations |

| Pascal | Pascal | 2016 | Blaise Pascal | Mathematics, probability theory, Pascal’s triangle |

| Volta | Volta | 2017 | Alessandro Volta | Electricity, inventor of the electric battery |

| Turing | Turing | 2018 | Alan Turing | Computer science, codebreaking, Turing machine |

| Ampere | Ampere | 2020 | André-Marie Ampère | Electrodynamics, Ampère’s law |

| Hopper | Hopper | 2022 | Grace Hopper | Computer programming, developed first compiler |

| Blackwell | Blackwell | 2024 | David Harold Blackwell | Statistics, game theory, first Black member of US National Academy |

| Rubin | Rubin | 2026* | Vera Rubin | Astronomy, dark matter research |